In The News: Print

Learning Medicine the Hard Way -- in Rural Kenya

While most first year medical students yearn for the day when they will begin clinical training, a rural clinic in Kenya where a microscope and a stethoscope are the principal and nearly the only diagnostic tools, where malaria, cholera, leprosy and VD are the most common problems, where psychiatric complaints are the province of the trial medicine man and where health care sometimes consists of sincerely hoping the patient will get better, is not usually what they have in mind.

However, for Arnon Krongrad, P&S '84, his summer as an Operation Crossroads Africa volunteer was an extremely rewarding, if precipitous and demanding, introduction to clinical medicine in an extraordinary primary care setting.

He was one of eight Americans - six medical students, one nurse and one physician - who made up a health care team assigned for six and a half weeks to the Tom Mboya Health Center on Rusinga Island in Lake Victoria, Kenya. In addition to the se foreign volunteers, the center was served by a staff of fifteen local health workers and was the only health facility for the 15,000 people of the island.

"We generally saw about 50 patients a day," he says, "and at first it was very frightening. Two medical students would be sent together to examine a patient and I hadn't the slightest idea what to do. However, we learned very fast, especially since malaria was the most common disease by far, and a few others appeared very frequently."

"I did histories and physicals, poured medications, checked pregnant women, observed all aspects of the clinic operation and by the end of the month I could run the pre- and postnatal clinics by myself and most of the outpatient unit. It was a great feeling to be able to say ‘I know what to do for you." Take this or do this and you'll feel better.'"

Although the clinic was in a concrete building and had running water, most of the patients lived in mud houses and bathed in the lake. There was very little salt in the diet, perhaps accounting for the fact that the average blood pressure was 100/65. The pressure of one of the American volunteers dropped from 120/80 to 90/50 during her stay.

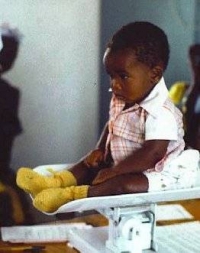

"Hypertension was virtually non-existent by our standards," said Mr. Krongrad, "although if a patient's pressure reached 120 we gave him Phenobarbital. We didn't see any heart disease, cancer, diabetes, or obesity. We did see intestinal and body worms, scabies, polio, thrush, and tetanus, and there some malnutrition, especially in children, for which the center ran a nutrition clinic. There was no lack of food, but education about nutrition was sorely needed. Parents didn't know how to feed very young children or how to eat a balanced diet. We tried to encourage longer breast feeding and fewer children, but no birth control methods were available or taught. The men are polygamous while women are monogamous. Most women had about ten children, many of whom diet. The Rusinga population growth rate, however, is four percent per year, the highest in the world, even with a 22 percent mortality by age five.

"On the whole, though, the adult population was very strong and healthy. The government is beginning to emphasize preventive health care and we gave some personal hygiene and public health lectures in the schools. We also discussed religion, sexism and American politics. The only time racism was mentioned was in connection with American problems.

"The clinic was an unusual beginning for me in medicine, but I think an important one. We have a good pharmacy, but there were no blood tests, x-rays, cultures, or surgery. There are few doctors in rural Kenya and the nearest hospital was at least four hours from us. We once had a baby dying of malnutrition. To take her to the hospital would have required a Land Rover to drive 15 miles on a bumpy road to the ferry, finding the ferry man or a canoe, paddling through a strong current, walking several miles to a mission on the mainland to find a car and then driving two hours on dirt roads to the hospital, all the while resuscitating the baby. It was impossible and the baby died.

"I imagine that I will have a different perspective than my fellow students when I begin clinical work here. I am really pleased that I had experience. After all it was in Africa that I gave my first injection and witnessed my first delivery, by the light of the setting sun and a kerosene lamp. I must admit that I benefited a lot more than the Africans benefited from me."